Excel Centers help dropouts find new paths to education success

Editor’s note: Despite the disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the Excel Centers featured here are continuing their work. Beginning in early April – and until public health conditions improve and restrictions are lifted – students will attend all classes online, following an E-learning curriculum designed by Excel Centers faculty.

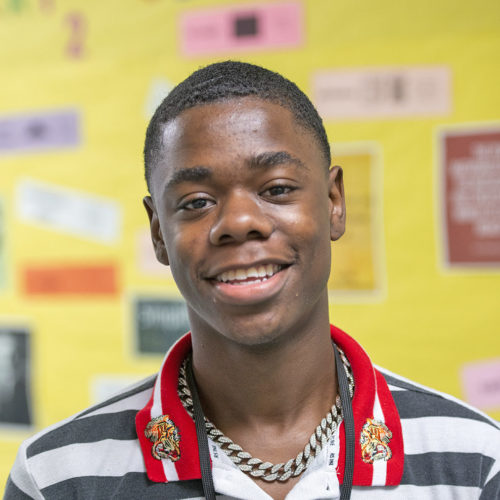

Amidst pomp, applause and smartphone paparazzi, the high school graduates from the Class of 2019 started trickling into historic Lisner Auditorium on the campus of George Washington University. They made their way to the stage in white and green robes, waving at their teachers, coaches and families. Some in the audience cheered while holding cardboard cutouts of graduates’ faces. On their true faces, the delight was palpable.

The D.C. Excel Center’s most recent graduating class included immigrants, single parents, and others who fell through the cracks of the school system for a variety of reasons, including pregnancy, disabilities, mental health issues, bullying, or simply lack of access to the right resources.

As dropouts, they had been among the tens of millions of adult learners in the United States who lack basic education and literacy skills. Even in the nation’s capital, considered a “highly educated” city, more than 33,000 working-age adults lack a high school diploma or its equivalent, according to census data.

The absence of a diploma exacts a high price in the U.S., where the number of jobs that require college degrees or other credentials beyond high school have grown rapidly in recent years – a trend that shows no sign of abating.

In an education system that offers few nontraditional schooling options for adults seeking a high school diploma, Excel Centers leverage state funding to fill a gap left open by online programs, GED prep classes, and workforce training programs.

And Excel offers more than a diploma. Students can take classes toward industry certifications, which are especially valuable to the student population served by Excel Centers nationwide. For students, what makes the Excel model work are support services such as drop-in child care, transportation stipends, and personalized coaching that affects their lives outside the classroom.

By the time the Excel Center opened in D.C. in 2016, the model had already proven effective in its birthplace: Indiana. There, six years after its 2010 launch as a single, adult-serving charter school in Indianapolis, it had grown to a network of 14 schools spreading beyond the metropolis and into rural parts of the state. It primarily serves communities of color.

As school choice advocates in Indiana hailed Excel as a successful example of charter school innovation, Goodwill affiliates in other states, including Texas and Tennessee, took notice. They wondered if a high school for adult dropouts could address challenges of access and equity for adult students in their own states. In 2014, Goodwill in Indiana started licensing the Excel model to its counterparts in other states.

However, because education laws differ by state, the model had to adapt to a new regulatory and legislative climate wherever it went. For instance, in Austin, Texas, the state only approved the Excel Center to serve students 26 and older. That’s because Texas law caps the high school enrollment age at 26. After that, the only option is a GED.

While the Excel model can accommodate certain modifications, its founders in Indiana decided early on that some elements were non-negotiable. Betsy Delgado, who leads education initiatives at Goodwill of Southern & Central Indiana, put it this way: “No matter where the model went, those pillars stayed.”

One such pillar is that Excel combines in-class instruction with online learning – a lesson learned the hard way during the program’s first year in Indianapolis.

At first, Excel used an all-online curriculum that offered students no face-to-face teaching. That year, only four students graduated – from a class of 300.

“It was clear what we had wasn’t working,” Delgado said. “It was also clear that we needed to build something unique for adults, something that understood, not undermined their needs.”

“We thought: ‘Rather than doing what’s been happening across the country – putting adults students through online programs – why don’t we look at offering in-class instruction?’” Delgado recalled. “We decided to leave no more than about 10 percent of the curriculum online.”

At all 24 Excel Centers operating in five states, primarily in the Midwest and South, students work at their own pace. Each school offers five eight-week terms throughout the year, and enrollments are open at the beginning of each term.

Another pillar of the program is that each student is assigned a life coach – an advisor who partners with students to maximize their personal and professional potential. Earning a high school diploma is a definite goal, but life coaches do more than just help students reach that commencement stage.

Adult students typically juggle jobs, family life, and other responsibilities – leaving little time for academics, let alone co-curricular activities. Coaches help students create schedules and organize their time. And they try to build trusting relationships with all students so that, when obstacles occur, they can help students surmount them and stay on track.

Students also say their life coaches have encouraged self-discovery and creative thinking toward goals beyond graduation. Some said they see their coaches as role models – often because the coaches have traveled a similar educational path, dropping out when young, and then returning – and succeeding – as adults. This is especially true for students from communities beset by generational poverty.

Research shows that adult students who escape such poverty usually cite an individual who made a significant difference for them.

At Excel Centers, those success stories are multiplying. Since 2010, more than 4,500 students have graduated from Excel Centers nationwide. In Indiana alone, over 70 percent of graduates are employed. Many have gone on to enroll in college, others breaking through with better jobs and higher wages. For others, Excel has allowed them to finish a long-delayed journey and set an example for their children.

The network of Excel Centers continues to expand, with eight new schools expected to open soon. With that growth, more inspiring stories of its students – like the ones shared below – are sure to unfold.

The stories in this issue of Snapshot were written by Aditi Malhotra, an independent journalist based in San Francisco. Her work has appeared in Slate, TheAtlantic.com, the Chicago Sun-Times, and PBS, among others. She also worked as a New Delhi-based correspondent for the Wall Street Journal.

Photos by Carolyn Becker, Greg Campbell, Brent Smith, and Shawn Spence