Climbing a broken ladder: In Memphis, a single father returns to school

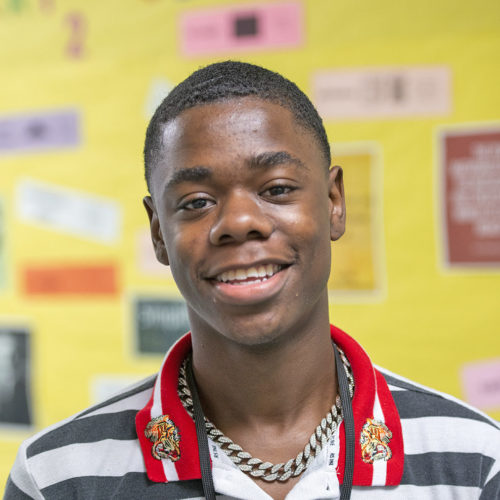

MEMPHIS — Tavarus Isom drives into the school parking lot at 8 a.m. every weekday. His classes don’t start until 45 minutes later. But Isom, a single father of two, can’t afford to be tardy. On the contrary, maintaining the buffer time is crucial for the 28-year-old.

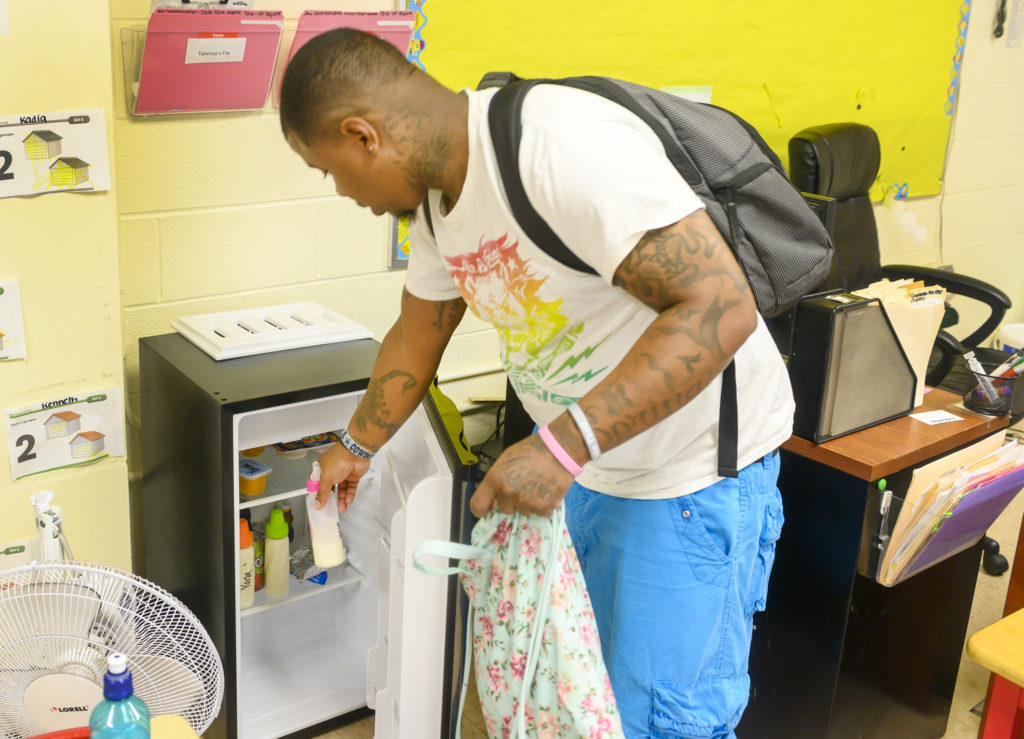

“This is like the busiest part of my day,” said Isom, walking through the halls of the Excel Center in Memphis on a Wednesday morning. On his left shoulder, he held his 6-month-old daughter, Yana. A blue floral-printed bag hung on his other arm. Inside it were milk bottles, diapers, water bottles labeled with his children’s names, and some snacks. Tailing Isom and Yana was 5-year-old Ashton, who was going to spend the day with his sister at his father’s high school, since his own school was on summer break.

“I’m coming back to school not only for me, but also for my kids,” Isom said a few hours later, between classes. His eyes looked weary.

Isom’s story illustrates the challenges that many young African-American single fathers from low-income communities face in maintaining a steady schooling path.

Recent research suggests that black men fare worse economically than their white peers, even if they are raised in households with similar incomes and educated similarly. It is well-established that African Americans are poorer than the average American.

Despite aging out of the traditional school system, some students, particularly single parents like Isom, are motivated to break the chains of generational poverty and low education. The Excel Centers meet them where they are, helping them climb broken ladders.

Isom was in 11th grade at a public school in Mississippi’s DeSoto County when he dropped out of school. After an altercation with his mother, he decided to live with his father in Bartlett, Tennessee, northeast of Memphis. Isom’s parents separated when he was much younger, he said. In 2008, after he arrived in Tennessee, three public schools in Memphis denied him admission because he was older than 18, the maximum age for enrollment in the city schools.

After the rejections, Isom decided to put full-time school on hold and focus on getting a job. At first, while working, he pursued the General Educational Development (GED) program. A few months in, Isom was sure he didn’t like it. He couldn’t point to a specific problem, but said he just didn’t feel motivated. Soon after he enrolled in the program, Isom dropped out.

His educational trajectory flattened further when life dealt him two harsh personal blows. In 2018, one day after the other, his best friend and his younger brother died.

By the time he arrived at the Excel Center, in January 2019, Isom was 28 and a father of two. The fact that he had no high school diploma had already made it tough for him to find a job that could sustain him and his children

Research shows African-American fathers are more likely than their white peers to face barriers in parenting related to poverty. More than twice as many black children as whites grow up in families living below the poverty level. They are also more likely to live in poor neighborhoods, where community services are often insufficient to fill gaps in household resources.

“I just knew I didn’t want my son to grow up in the same situation that I did,” he said. This thought motivated him to stay on the path to education.

At his age, however, Isom couldn’t gain admission to a traditional public high school. And even if he could, few such schools are equipped to meet the needs of students like Isom – returning adults who must balance work, school, and parenthood. Isom needed flexibility – in curriculum, pace, class scheduling, and in the overall structure of his schooling.

There was one other potential deal breaker in determining whether Isom could return to high school: child care.

In Memphis, where the proportion of unemployed young people is among the highest in the country, the Excel Center is the one high school that serves only adults. It allowed Isom to resume his education and graduate with a diploma, not an equivalent certification such as the GED. It also offered child care – a vital service to many at the Excel Center, whose students largely come from predominantly low-income, African-American neighborhoods in Memphis.

At school, Isom gravitates toward others his age.

That Wednesday morning, he walked into an economics classroom and headed straight for a seat in the front row facing the whiteboard. Before choosing his spot though, he’d already chosen his company.

He sat next to a young woman named Keotany, introducing her as one of six or seven in their group of “like-minded” students. They’re all over 25. And, everyone in the group is serious about earning a high school diploma, Keotany and Isom said.

“No drama,” Isom insisted. “I’m not trying to be here any longer than I need to be,” he said, at times bemoaning younger students’ tendency to disrupt the class. Keotany agreed. More than half of the students in the Memphis Excel Center are 18-21 years old – younger than Isom, Keotany and others in their group. The oldest member of this group is 55-year-old Bobbie Robinson, whom Isom calls his “school mom.”

The classroom disruption isn’t ideal, but it doesn’t sway Isom. He’s resilient – in school and in life. On his right wrist, he wears a black rubber wristband with the words “Never Quit” emblazoned in neon green.

“It was rough for me, not getting into schools when I was so close to getting my high school diploma,” Isom said. “I felt like I got robbed of an education.”

His mission now, he said, is to show younger kids that it’s never too late.

“The Excel Center will help you if you want to help yourself,” he said.

The stories in this issue of Snapshot were written by Aditi Malhotra, an independent journalist based in San Francisco. Her work has appeared in Slate, TheAtlantic.com, the Chicago Sun-Times, and PBS, among others. She also worked as a New Delhi-based correspondent for the Wall Street Journal.

Photos by Carolyn Becker, Greg Campbell, Brent Smith, and Shawn Spence